By Jasmine Jones

I spent the first 24 years of my life in Missouri, specifically Southeast Missouri. I’ve never called another place home. As a child, I remember pressing my face against the car window and memorizing every turn we took to get to Grandma’s house, the grocery store, school and mall. I was afraid of growing up and getting lost. I thought the way adults navigated the world was the result of a higher wisdom, something studied at night when us kids were asleep, something that tucked into their brains at a certain age and solidified. I did not know the simple answer: Their knowledge was only the result of living in a place, calling it home and repeating actions until they became ritual.

I left Missouri and all the roads I knew on a Sunday in July last year. My parents stuffed my mattress into their car’s trunk, and I stuffed my car’s trunk with books and clothes and a chair I had painted pink for my very first adult apartment I had moved out of a month before.

Why must everything end too slow and so soon? I thought. That was how I felt about leaving Missouri. It was too slow and so soon.

As we drove across America, the land became tumble-dried. We traversed through the flat fields of Nebraska, the hills of South Dakota, and the evergreen slopes of Montana and Northern Idaho. Like a parachute in motion, the ground broke into bright yellow and green hills as I drove my car on the fourth day of our journey through a landscape I’d learn to call The Palouse.

The city of Moscow, Idaho, nestled in the middle of The Palouse, introduced itself with a sign. “Heart of the Arts,” the sign stated. As I drove through the streets for the first time, I frantically absorbed the businesses and houses that populated the sides of the road. This was my new home, where I’d be studying creative writing and teaching for the next three years, and I was seeing it for the first time. I felt the need to memorize the whole of it, fit it immediately into the lore of my life.

Suddenly I was in a new apartment, alone, and I knew nobody. When I looked out the window, I saw nothing but a stained wall just tall enough to block my view of the sky.

I knew I’d have to work to build community, so I started by meeting other graduate students for long coffee dates and walks. I became a regular at local coffee shops; the baristas learned my name, and I learned theirs. Once the semester started, I taught and read and wrote and attended poetry readings and hiked mountains and did all the creative writing things I’d dreamed about for years from my old bedroom in Missouri. On walks after class, I kept saying to my friends: “We’re really here. We’re in Idaho. Doing this.” It was a reminder to hug this gift of a place. To be intentional in how I fashioned it into a home.

Of course, it was not always easy. On my 25th birthday, I realized it was the first birthday of my life I wouldn’t eat cake at my grandma’s house. A few weeks later, my aunt sent photos of the family eating Thanksgiving dinner, the table full and without me. And then, when my parents called to say my childhood cat Buster hadn’t moved from the living room chair in days, I knew I would not pet his soft head again. They called the next day to say he’d passed away. Never in my life had I felt so far away.

My homesickness leaked into the essays and stories I wrote for school. There was so much I wanted to say about the strange place I had called home, so much I was feeling, yet often, I could only write about the Mississippi River. It became a joke amongst my friends, how much I mentioned that Midwest river and its muddy banks. I wrote about the river, and I wrote about the trees. Oh, all those deciduous green, leaf-heavy branches of Missouri. I missed them. In Idaho, I still could not name the trees I passed on my walks and drives. I did not know the difference between a cedar, fir and pine. I kept envisioning maples.

Despite my longing for Missouri, when I finally visited during winter break, I found myself dreaming of Idaho. “There are cedar trees here,” I said in the car on our drive home from the airport. I searched for evergreens everywhere and pretended to be in the Northwest. I felt split between two homes, constantly longing for one or the other. For Missouri or Idaho. Never content in the place I stood.

My friend Emily speaks often of this feeling. She had moved from Illinois to New York City after college and told me it’s a curse to be in love with two places. You’re home, and yet, you’re never home.

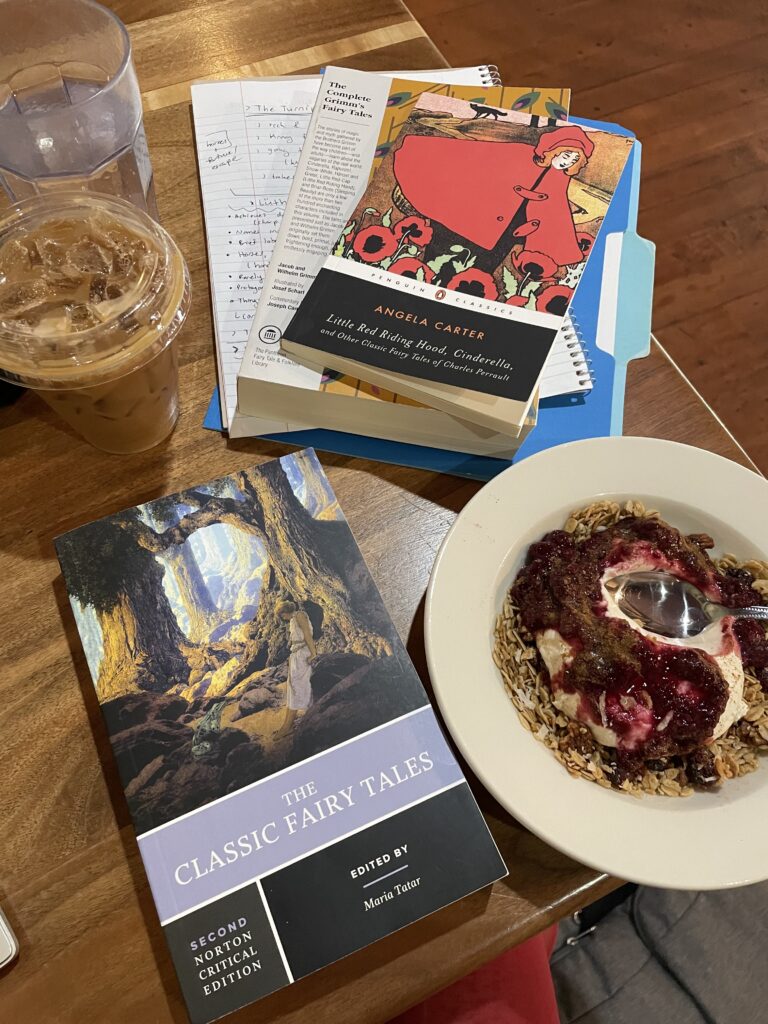

When you have two places to call home, this split will always be there, but I’ve learned ways to stitch my time and love between the two. For example, the other day, I took photos of my view from my favorite coffee shop in Moscow and sent it to my mom and grandma. My grandma texted, “I love seeing what you see.” She sent me back a photo of the snow in the woods outside her house. The backyard in her photo was familiar to me, a place I had explored with my cousins as a child. The coffee shop in my photo was new to her, but not to me. It is also a familiar place for me now: that high barstool with a window view where I write short stories and get interrupted often by friends.

Our homes are created by us. This is what I’ve learned from living in and leaving Missouri. We can have a hometown, yes, and we can still love it, still connect to and return to it once we’ve moved away. We can also find a new place where we know no one and nothing; we can make it known through our actions.

I was in a modern dance class recently where our instructor explained how our bodies take up positive space, and everything else around us that is untaken is negative space. This makes us all constant claimers and returners of space. Moving from one place to another to another.

I am beginning to believe what is new and what is old does not matter so much. It’s what’s returned to and repeated that becomes home.