Hannah March Sanders didn’t initially want to be an artist (both of her parents are artists). She didn’t want to marry an artist. She didn’t want to have kids.

Now, she holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in Studio Art: Printmaking and is a tenured professor with the Southeast Missouri State University Department of Art + Design. She is married to artist and professor Blake Sanders. They have two sons, an eight-year-old and a three-year-old. And she loves the life they are creating together.

“Basically, I have no idea what’s good for me until I try it,” she says.

Here, March Sanders talks about the challenges of being an artist mother, collaborating with her children and incorporating feminist practices into her artmaking process. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mia Pohlman: You mentioned you didn’t think you wanted children and were kind of hoping to make that decision [to not be a parent] and then chose something different. How did you come to motherhood and decide that was something you wanted to do?

Hannah March Sanders: Well, I think it was just meeting Blake. I really only wanted to have kids with him. Not because he pressured me or anything; I think it’s just pheromonal, or just love, probably. And I don’t regret that, either. I’m not the kind of person who thinks you have to have kids to fully experience life or enjoy life; you can engage with other people’s kids or just not be into that. They’re fledgling humans — they’re not fun for everyone. They’re a lot of work, you know? And we have plenty of humans on this planet — you don’t necessarily need to make more. There’s plenty of people who will. So, basically, it was just that — it felt like an impulsive decision, because ultimately, I felt like I didn’t have to think about it, so it was more of an instinctual, gut decision that I made long before we started having kids.

I loved [your illustration] I saw on Instagram — your panel that said, “How two brothers talk to each other,” and one of them was saying, “No, no, no,” and the other was saying, “Yes, yes, yes.”

Yeah, [our sons] yell at each other a lot. It’s just like a hobby of theirs. They’re not actually mad. They’re often annoyed, and they do get mad sometimes.

That’s part of the rights of siblings, though, right?

Yeah. I always wanted a brother, because a lot of the girls I knew wouldn’t have wanted to do the things I was doing. But that was just my limited perception and people I happened to know.

Something I love about your art is how candid it is and how raw and honest. Can you talk about how you’ve cultivated that style, and then I’m also really interested in how do you know what to share and what not to? What is that balance — or is there one?

I think how I cultivated that is sketchbook journaling — which I have [sketchbook journals I’ve sketched in] back to 1992 — and sometimes, I have overcurated even what I put in my private sketchbooks. When I’m dealing with hard stuff, I just didn’t want to write about it or put it down, and later, I’ve kind of regretted that.

But I think working in this space [of the sketchbook] is like, no one cares what you do in there. And these have been my work that was most well-received of anything that I have made. Because when I was in grad school, I was trying to create narrative work and tell stories, and I was really failing at that in my larger artwork pieces, but then anything that was in my sketchbook was more engaging, so I did some things where I tried to make larger-scale prints like sketchbook work, which kind of is what led me into comics, a combination of text and image and framing and panels and pages and all that kind of stuff.

That was a long journey, but I think doing that, I realized that part of what was engaging was just the honesty and directness and not being afraid to embarrass myself. Because I’m pretty much going to embarrass myself, anyway, is what I’ve learned, and I’m going to piss some people off, and I guess the stuff I avoid the most is the stuff that I know people in my life are reading and they might read wrong or be really offended by. So, I don’t talk as much about other people’s lives and stuff with other people. … So sometimes, it is embarrassing still to put that stuff out there, but I started probably in 2008 or so, publishing online more of my sketchbooks, and that kind of wore me down a little bit, I guess, made it feel more OK. And I just try to be funny, too; I think that helps.

[Your illustrations are] so funny. I love it.

Because even if it’s like a sick burn or something, if it’s funny, it’s OK. I really respect comedians because I feel like they can say more true things, because you’re going to laugh at it, and you’re not sure if their intention was to say a sick burn or something or to make you laugh or both, so it just makes it more enjoyable. I’ve had people get mad at me on the internet before.

It’s kind of the place for it, right?

Yeah. I mean, it’s going to happen anyway, right? And I’m not the person to make just the cute art.

With that, I feel like something you’re so good at is drilling into that one detail or observation, and that’s what makes it so honest or truthful or relatable. How do you do that?

Probably obsessively thinking about something after it happens. And telling jokes for myself, because things like email, for example, is an easy one that everyone understands. I don’t know, just the same bad things continue to happen on emails every day, and so you just distill your experience of it, and to me, if i didn’t make fun of it, it would drive me crazy. And so, after making a comic, sometimes, I’m able to breathe about it and not write the mean email back.

Motherhood as a topic for art has been in conversation a lot with a lot of artistic circles, with a lot of people saying they have felt like motherhood isn’t a valid subject to make art about. Not that they themselves have felt that way, but they have perceived that others in the art world feel that way.

Oh, definitely.

Have you experienced that at all?

I mean, sometimes, male colleagues will say to me that something’s too personal to discuss, and I’m like, well, because it’s not a part of your daily experience, maybe it feels that way. And also, a lot of the aspects of motherhood, if you don’t talk about them, there’s no accommodation for them in the workplace. And there’s still a lot of work to be done on that front. As someone who didn’t get to take maternity leave either time I had children, it was pretty bad. And I had C-sections both times that were very difficult, so to have to work in my physical job around a lot of chemicals and stuff and for people to be like, “Oh, that’s too personal,” well, the chemicals we work with affect our reproductive organs, they affect the unborn child. And so, there’s just a lot of that stuff that still isn’t discussed that when I do bring it up, often people will nod, and then if they aren’t in that same genre, if they’re not a pregnant woman, they’ll be like, “Oh, OK,” but then they won’t do anything about it.

What’s helped me is I’ve joined up with some organizations like the Artist/Parent/Academic organization.

Is that a national organization?

Yeah. … I have a support group of women — there’s one of us in every time zone across the country. And we mostly chat on a chat app, but we Zoom sometimes, we’ve had shows together. We share opportunities with each other. We read each other’s cover letters for stuff, we share pictures of our kids. So, that’s been very helpful. …

As a mom, you don’t always have time to write the grant application, but it doesn’t mean you don’t need the money. … And [we need] more residencies that are family-friendly. Because those are incredibly limited, as well.

I have never even thought about that.

And there’s a real divide, like, some residencies are like, “We don’t understand why you would want your kids with you; the point of a residency is to get away from your normal life and focus and make work.” And other residencies are like, “We understand why you have nothing else to do with your kids, or maybe you want your kids there.” But that second category is very rare. And if they want to be in the first category, to me, they need to offer childcare options. …

There’s a hashtag … called #ArtistResidencyAndMotherhood. … You can sign up to do a residency as a mother, and it’s self-guided, and you’re not leaving your home, so it’s really like an exercise for yourself, and you can share what you made with the hashtag, and it’s just kind of talking about how, as a parent, you’re sometimes trapped in the home — not always in a negative way, but sometimes, it does feel that way creatively, because you can’t get out and make stuff. For [Blake and me], we just really adapted what we make and what materials we use to parenthood. And that’s what allowed us to survive that period, which is honestly still ongoing. Because I can’t have my baby in the studio while I’m working with nitric acid, you know? It’s a lab environment. That’s a chemical required for some of the printmaking processes that I do. And so, rather than pay a lot of money for childcare or go in at midnight after they’re in bed, I’m just going to work with fabric at home.

Those are some things that have helped me. It’s still really difficult, and some days, I’m very frustrated about it. Not to the point where I regret my life decision to have kids, but there’s just not enough time in the day. Like, more than wanting childcare or anything, I just wish I could add like five hours to the day where I felt well-rested. ‘Cause sometimes, there’s like one hour of the day where I feel well-rested, and then I’m, like, cleaning Cheetos up off the floor or something.

I love that reality, though. Do you feel like some of that gives you inspiration for the work that you’re making?

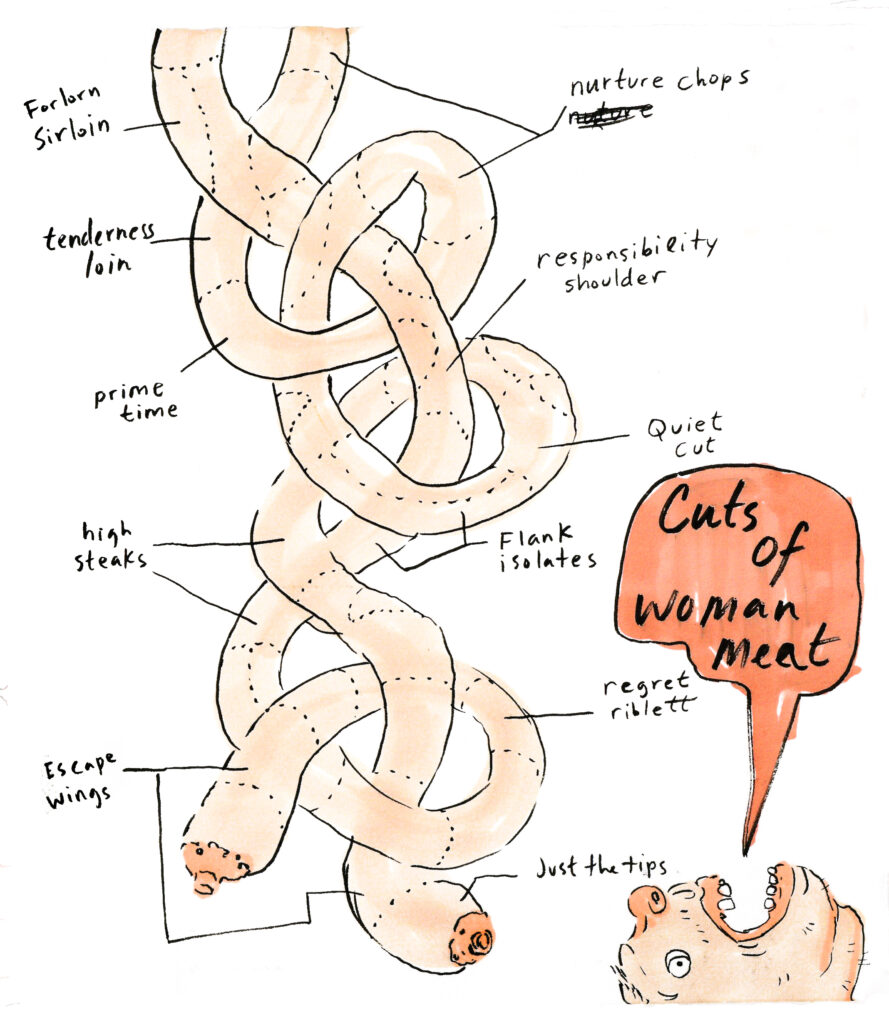

Yeah, definitely. Scribbling down a comic in my sketchbook has been good and easy to do for that, and my kids will draw with me and stuff. But creating something that’s finished that I feel like I could publish, that’s really difficult, because writing, for me, I need more quiet and mental focus than I do for doodling. … And our fiber arts has been good to work around kids with. A lot of the traditional quote, unquote “women’s work” stuff is safe to do around kids. So, we’ve embraced feminism not just as an idea within our work and as a concept, but also the practices of it.

And it’s unfortunate that so many schools across the country have been getting rid of fiber arts and jewelry metalworks. Like, when cuts were made, those were always the first things to go, and they like to say that’s not sexist, but it is, because that art is not always valued as much. And I’ve had other art professionals that I’ve trusted be like, “Oh, that’s too crafty,” or, “That’s not art,” but when I went to the [Whitney Biennial in New York City], all the work I saw there was amazing, and then we went to the craft museum that had just recently been renamed to something else, because “craft” is a dirty word sometimes. All the work at the craft museum was just as good, but it was better-made. It just had typically better use of materials and was sturdier and better structural build, and so, I learned like, “Oh. Yeah. there’s not really any difference between these.” And sometimes, that is just a sexist judgment or a lot of People of Color and queer people work with craft material, too, because it’s a laborer task. … So, that’s something I think about a lot.

I did just rewrite our printmaking curriculum to incorporate fibers into it at SEMO, because I was worried that fibers was going to go away with the dissolution of our art education program. … [Fibers is] what we do a lot of, so that’s my little trying to save some feminist aspect within our curriculum.

On the flip side, looking at parenting as creation and as art, do you see raising children also as shaping and artmaking?

Yeah. … I mean, you are the materials of your kids, at least as you form them, but then, once they’re born, they have a lot more influence that are building them. So, I think if it’s a work of art, it’s one that’s community and collaborative, and you don’t really have control over, in a good way. I mean, I feel like if you had control over everything your child experienced, they’re going to have a really rude awakening when they do get out in the world and move beyond you. And also, who wants to make perfect little copies of themselves? Just be yourself, and they’re going to be who they’re going to be.

So, we do collaborate with them. They give us a lot of ideas for our work. I remember when I was a kid, I used to ask my mom to make me things out of clay, because she’s a potter, and then sometimes, she would keep making those things, because she was like, “Oh, it’s actually interesting to keep making this.” So, I think that collaboration is very common among other parent artists that we see.

And sometimes, it’s frustrating, because you’re just trying to get something done, or I would typically spend a long time drawing something, and I’d go to the bathroom and come back, and a child would’ve scribbled over all of it, but I’ve kind of learned to incorporate that into it. And learned ways to work with that, too. Like, I’ll give them a lighter-color pen, and then I’ll go over things with a darker-color pen, to make selective choices, and maybe one day, we’ll flip it, who knows?

But yeah, I feel like I can’t fully speak to parenting, because I have kids who are eight and three, and there’s all these other stages of that, that I haven’t gotten to yet, and just knowing how little I knew about how this point of the experience would be when I started, I’m just assuming I’ve got no idea what’s coming next.

Thankfully, Blake is an incredibly good parent. Like, I think if I was doing this on my own or with a different partner, I wouldn’t be doing as well with it. He’s an incredible cook. He does all of our laundry during the year, does most of the pickups and dropoffs, because [my] academic teaching full-time is a lot, especially during the year. And yeah, he makes a lot of art, too. And yeah, I think as a couple, we’ve been able to help each other as artists, as well as, as parents, just by taking on different roles.

How do you choose what you prioritize? What are you learning within that process?

I feel like all that got turned on its head in the recent years. I don’t know if the pandemic did that for me or having another kid or just how those things have changed my mindset. I’ve been having a really hard time prioritizing. So yeah, I’m not sure if I really have an answer for that. I mean, with work, I try to prioritize the students. That’s really hard to do sometimes, because there’s so many other “urgent” quote unquote things going on, like the spreadsheet is due. So, I try to prioritize them during the week, especially during their class time and during 9 to 5 Monday through Friday, responding to them promptly and things like that.

On the weekends since the pandemic, I’m trying to prioritize family and myself more, and sleep. Because those are things I did not prioritize my first years here. Yeah, so that’s something I’m trying to introduce. And it’s really hard not to feel guilty about that or to feel that those things are as valuable. And it’s difficult to justify those things to your workplace. So, trying to do things like schedule time to exercise, rather than being like, “Oh, I was going to go do yoga, but I guess I better do this work thing, instead,” be like, “Oh, nope, yoga’s on my schedule, so I’m going to do that.” … If you just use that kind of language about it, I find that helpful.

Where do you think that comes from, that pressure that the home isn’t as important as the workplace?

Well, I mean, at work, I’m someone who does get stuff done and does it well, so people want me to do more things. So, being successful sometimes is a hard cross to bear. But yeah, I think it’s that. I think it’s just my personality to some degree. I like to complete things, I like to do them well, I like to be efficient and fast at stuff. I like checking off lists. It is very satisfying.

So, there’s that, and then, there’s mothers just aren’t valued as much in society, you know? Just look at the wage gap. Just look at anything, really. Even just casual language I’ve heard at work — people don’t even realize what they’re saying about stuff sometimes, and they’re not valuing women in the same way they are men.

Or [the perception] that motherhood isn’t work.

Well, there’s that, too. And then, we run into the arguments of the people who chose not to have kids or didn’t have kids for some reason, and then they’re like, “Why should I have to work night classes because Hannah has kids?” And that’s fair. And they ask, “Why do I need to pay more for health care? I don’t have kids.” But I think some stuff — and this is probably easier for me to say as someone who needs those things — I feel like, I pay for other people’s stuff that doesn’t benefit me, and that’s how the communal system works. But there’s a lot of things that just aren’t figured out.

… I didn’t really have professors who had kids, particularly not women professors [when I was a student]. A lot of them wouldn’t have gotten the job and been in the place they did if they had had kids. So, people are like, “Oh, that’s old news, we don’t need feminism anymore.” It’s like, well, this is one generation before me, and I’m still struggling with this stuff, so I don’t really think it’s old news and all done and said for.

That’s really interesting, this idea there weren’t parent artists that you had as role models to pass down how to do that. What would you say to other women and men who are also parents and creators and artists at the same time? What wisdom would you want to pass on to them about making and parenting?

Well, I think you do have to find other people in that situation to talk to, because a lot of times, people either don’t care about your issues or don’t understand, because you’re speaking a totally different language from them. So, finding the Artist/Parent/Academic support group was really life-saving for me, and I mean that completely seriously. Because sometimes as a parent, you fall down a deep, dark hole where you’re like, “Does anyone even hear me or see me? How am I going to get through all of this?” So, I’m lucky I have a good partner — and that [struggle] still happened with me. So, I think that was most important.

And then, I think environmentally-friendly practices are health-friendly practices. … I think getting over those hurdles of [the idea that] safe practice is not professional practice [is important]. And some of that just takes experimentation and work.

… And curating whatever you’re looking at — books, movies, social media feed — to have people in it that are going through the same thing as you. A book that really turned the corner for me was “A Life’s Work,” by Rachel Cusk, and she’s an author talking about … how there’s all of these opposing things going on once you have a kid and are still trying to do creative work. Like, OK, so, maybe you manage to pay a babysitter to come, and then the whole time, you’re just pumping milk and looking at pictures of your kid, and you can’t focus, and you never make anything, and so you feel like you’re just throwing all this money away on not getting some work done, and then you just want to be back with your baby, but then you get back with your baby, and you’re like, “Oh, I need to make some art.” … It’s really hard to live in the moment. So, that’s something I’m working on. So, I think if you can find other people that are doing a good job balancing that, it’s great.

We don’t have any family close to here — my parents are older, Blake’s parents are kind of doing their own thing — and grandparents don’t choose to be grandparents necessarily, so you can’t expect them to watch your kid a certain number of hours a month or year or whatever, but I think we would be living a total different life if we had one set of parents in town or both sets of parents in town. And that’s something Blake and I know from personal experience, because we spent a lot of time with our grandparents, so we know our parents had that benefit. But we don’t have that benefit. So, I don’t know; if intergenerational living is possible — it may not be right for us, but — I could see that being really beneficial.

Is there anything else you would want people to know?

… [Blake and I] both have creative parents, and I do think if you grow up seeing that, it increases your chances of going into a creative field, because I guess one thing I want to mention as an educator and something I want to get out as sort of a PSA is, you can go into an arts and creative field and be successful. We get a lot of pushback from parents, like, “If you want to get a degree in art, you need to also get a degree in something you can get a job in.” It’s like, “No. We’re small business owners. We have a lot of business skills. We’re very flexible, we have a lot to offer to a lot of different industries.” Like, if I were to quit academia right now, I feel like I would have a lot of other job opportunities that I would be very qualified for, and it would just be about changing the language on my résumé. You become like a chameleon with what you’re able to do. So, I guess I would put that out there.

It’s important to expose your kids to good examples of a lot of different careers and walks of life and try not to let your biases get in the way. Like, I would be equally happy if my kid is going to operate a crane or go to school and get a degree in biology. I think there’s a lot of options for that, and also, once you make a decision on what you’re going to do, you can change that any time in your life. Once you’re doing something, it doesn’t mean you have to keep doing that. But I think a lot of us get very pigeonholed with the careers we’re exposed to and our assumptions about them.

So, having role models in a lot of different areas is very important. And most people have that, right, within their own family or their church or community group, the library. There’s a lot of places to get access to that kind of experience for kids. I just think that’s important, as someone whose field is looked down on quite a bit, as well, [with people saying], “You guys aren’t as smart,” and then, if they are complimenting us, they say, “Well, you were born with that talent.” It’s like, “No. This is a lot of hard work.”

I would agree with that — my art classes in undergrad, I worked the hardest in those classes and spent the most time on it. And it didn’t always feel like work, even though it was, because I loved doing it, and it was something that I was like, yes. But I spent the most time and put in the most work in those classes.

And you get too much art and music cut out of schools, and that’s why people don’t experience it from a young age or appreciate it. … If you don’t support the arts, it’s not going to become a part of people’s life anymore. By not supporting it, you’re not valuing it, and that’s setting an example for everyone else, too.

But that’s a really hard thing to convince people of, because people will say, “Oh, I can’t even draw a stick figure.” It’s like, “Well I could teach you to draw, if you come hang out with me for a little bit, and then if you try, spend some time on it.” I think some people have the mental alignment to want to do it more. Like you said, when you did it, a lot of times, you felt like it was fun. So, you kept doing it. And that’s the only really ingrained thing. But, I think, too, once you start doing something, you’ll enjoy it more.

So, it’s very much a learned thing that we’re not teaching kids as much of. So, I guess that’s all I would add as far as the lineage thing. I hope that anyone who is thinking about doodling or trying, quit judging yourself. If you have a sketchbook, you never have to show it to anyone, you know? You should just have one place where you can do whatever you want. Even if you don’t ever like any of the products of it, a lot of art is process-oriented. The act of doing it is good for you; it doesn’t really matter what it looks like in the end.

So, I wish it was still more of a gen ed. Everyone at the university has to take either music, theater or art class, so that’s good, and unfortunately, I see a national decline in liberal arts. People are not supporting it as much anymore, and that means those types of things aren’t required. It becomes more of a trade school approach.

And not education for education’s sake.

Yeah. And I think having that liberal arts thing, they may go in being like, “When am I ever going to use drawing or theater?” And it’s like, “Well, you have no idea.” I’ve never regretted any class I’ve taken. And I’ve taken all kinds of weird stuff in fields that I’m not working in now. But I don’t regret any of it; I think it influences who I am as a person.