Here is what the painting looks like: a pipe, black at the top where the mouth goes, then brown around the curve into the bowl, light illuminating the bend like the sun on a river from 8,000 feet up. Below the pipe, in black — precise, cursive letters — the words: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” “This is not a pipe.”

It’s “The Treachery of Images,” painted in 1929 by Rene Magritte, a Surrealist who — fittingly — considered himself not an artist but rather, a philosopher, and wanted to remind us an image of an object is distinct from the object itself. If our minds are confused by the pairing of this image with Magritte’s written text, let it be a testament to how readily and completely we let ourselves believe images of objects are the actual thing.

In her 1977 essay “The Image-World” from her classic collection of criticism “On Photography,” writer Susan Sontag grapples with a similar idea: the way we as a society give authority to the photographic image, and what the proliferation of our creation and consumption of photographic images means for us. She writes in a pre-digital and pre-social media era, and her words now seem prophetic.

“A society becomes ‘modern’ when one of its chief activities is producing and consuming images, when images that have extraordinary powers to determine our demands upon reality and are themselves coveted substitutes for firsthand experience become indispensable to the health of the economy, the stability of the polity and the pursuit of private happiness,” she writes.

Valuing photographs over actual experience as a way of making money, conducting politics and seeking personal fulfillment: she might as well be writing about social media and its profound influence in our lives in the 21st Century. We seek out many experiences for the photo so we can share it with others, rather than doing things for the experience itself. We confuse the image with life.

Life, Sontag writes, does not freeze moments or value one moment more over another, as the camera does. We capture blowing out the candles and posing in front of the sign, standing as a family after the ceremony and waiting in front of the stage at concerts with friends, anything that might be “worthy” of remembering, worthy of proving we did. Anything we want to be able to reclaim from the refuse of moments that fall behind us as time — that perplexing mortal conundrum — leads us further on.

Because life, which is the pipe, is a series of always-changing, fluid moments of motion that, try as we might, we cannot capture or possess. Photographs, which are not a pipe, are single moments frozen still in time, forever captured. Life says each of these moments are equal; we, as camera operators building our world, are constantly consciously and subconsciously assessing, making selections about what is more important, valuable, worthy. The reality is that as people who are mortal, life changes, and the very definition requires that it move. For the moment when that motion stops, life as we know it ceases. Overcoming time and distance, perhaps photography helps us grasp at immortality.

“Let us make human beings in our image, after our likeness,” the great mythic storyteller writes in Genesis. God says it. It is one of the foundational tenets of Christianity, this teaching that people are made in God’s image. It is a both/and: people are the creation, not the creator, and because we are patterned after the one who makes, we create.

The divine, in any major world religion, is often associated with or referred to as light; “photography,” which from Greek means “light writing,” captures light and draws with it. Through the use of a camera, we create images with light that freeze time, bridge distance, allow us to overcome those circumstances we are subject to that make us mortal, not divine.

In the mid-1800s, Sontag writes, as political and religious ideologies were being abandoned for humanism and science in the Western world, rather than turning to what could be seen in person, people turned to images. The camera had been invented by Nicéphore Niépce in 1816, Darwin would publish “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, poets and philosophers emphasized emotion and imagination as a response to the logic and scientific thought of the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th Centuries. A seismic shift was happening within culture as people swung from faith without reason to reason without faith, not yet understanding they didn’t have to choose between the two.

“The new age of unbelief strengthened the allegiance to images,” Sontag writes. “The credence that could no longer be given to realities understood in the form of images was now being given to realities understood to be images, illusions. In the preface to the second edition (1843) of ‘The Essence of Christianity,’ Feuerback observes about ‘our era’ that it ‘prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, the representation to the reality, appearance to being’ — while being aware of doing just that.”

People began to choose the image over the reality of what it had previously represented, Sontag writes. They knew they were choosing the copy, and yet, they preferred it. Ludwig Feuerbach writes a few years after the invention of the camera, Sontag notes, observing a trend that perhaps continues to this day with the use of social media — which we know does not often portray reality, and yet, we often choose to believe it more than reality until it becomes our reality. Twitter is our town crier and where we hold political debate; Facebook is our record-keeper; Instagram is our place to seek others’ approval, which we believe brings happiness. All these platforms drive capital.

And in this way, images are necessary for our society to continue existing in the way it does.

“A capitalist society requires a culture based on images,” Sontag writes. “It needs to furnish vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate buying and anesthetize the injuries of class, race and sex. And it needs to gather unlimited amounts of information, the better to exploit natural resources, increase productivity, keep order, make war, give jobs to bureaucrats. … The social production of images also furnishes a ruling ideology. Social change is replaced by a change in images. The freedom to consume a plurality of images and goods is equated with freedom itself. The narrowing of free political choice to free economic consumption requires the unlimited production and consumption of images.”

It is a difficult social critique, but, perhaps, one that is merited. The image as it is used in advertising shows us the lifestyles we could live if only we acquired the next thing; capitalism needs the image. Scrolling through the unending feed of images on social media stokes our need to fit in somewhere while it provides a distraction both from taking action toward social injustices and the mundanity of the struggles of our day-to-day lives. In some cases, as Sontag alludes, we are literally entertaining ourselves to death, as ideological divides are reinforced, mental health deteriorates and people do dangerous things for the photo or video post. We forget that we, too, are only images and must still reckon with our mortality.

While Sontag focuses mostly on societies that have acclimated to the camera in “The Image-World,” she also muses upon societies for whom taking a photo is an uncomfortable experience because their members worry the camera might take from them part of their soul.

“To presume that the image is absolutely distinct from the object depicted — is part of that process of desacralization which separates us irrevocably from the world of sacred times and places in which an image was taken to participate in the reality of the object depicted,” she writes.

In these societies, Sontag claims people believe photos retain some quality of the person it is created in the image of. On the other hand, societies that have completely separated image from subject and easily create and consume images are ones that have moved, partly through the use of images, from a sacred society to a secular one. These are often the societies that, because of higher standards of living, are able to move beyond taking care of their people’s basic physical needs to spending time, money and energy on entertainment. These are, perhaps, the societies that most deny the human condition of suffering. Images detached from the real they represent provide an escape through entertainment.

“[Taking photos] offers, in one easy, habit-forming activity, both participation and alienation in our own lives and those of others — allowing us to participate, while confirming alienation,” Sontag writes. “A society which makes it normative to aspire never to experience privation, failure, misery, pain, dread disease, and in which death itself is regarded not as natural and inevitable but as a cruel, unmerited disaster, creates a tremendous curiosity about these events — a curiosity that is partly satisfied through picture-taking.”

We take pictures of that which interests us; social media has, in a sense, reversed that motive so that we take pictures of that which interests others. Perhaps, in less dramatic terms, there is something, then, to the soul-stealing quality of the photograph as used by social media: to an extent, we have exchanged our free experience of reality, which includes joy, suffering and mundanity, for a search for well-curated images others might tap a red heart to “like.”

I can’t help but think that as our ability to take and share pictures has become more advanced, our trust in and respect for authority has decreased, a quality that perhaps goes hand in hand with moving from a sacred to a secular society. Although individually and within specific communities there is still certainly a pervasive respect for the authority of the divine, political offices and institutions, it seems that as a society, these figureheads no longer captivate the respect or garner the allegiance they have in generations past. We prefer ourselves and our own authority to that of another.

Today, what does hold authority in our society? Images. And the camera has the power to create them. I think this can most effectively be seen with the concept of modern celebrity, a phenomenon that has been largely created during the past 200 years since the invention of the camera. We so often bow down to celebrity — either the attainment or the replication of it — by trying to become famous ourselves (something that has become just within reach to anyone with a cell phone and social media account) or through trying to attain celebrities’ lifestyles through copying what we see them wearing, eating, drinking, doing in the photos that bear their image. Sontag writes photography is “acquisition,” and through images, it seems we can acquire experiences that are not our own.

Photography allows us to revere what can be seen, whether it is true or not.

When I look at others’ Twitter accounts, their profile photo is how I imagine them. Regardless of the fact the photo was taken eight days or two months or six years ago, I imagine them frozen that way, wearing that shirt as they drink their coffee, smiling that way as they type their ideas with their thumbs onto the screen. Never mind that today they might be sick or are not wearing makeup or haven’t gotten out of their pajamas; never mind that yesterday they shaved their head or last week they got a black eye or this morning their hair is thrown up in a messy ponytail, flyaways exploding in a halo around their face. Never mind that in real life, they got no sleep last night or yesterday their wife told them they were leaving or this morning their kid puked into their best shoes sitting by the door before preschool. As I read their thoughts on my screen, the tweeter is there, sitting at their desk, preserved in my mind as their photo, poised, tranquil, smiling. They have no doubts about sending their thoughts out into the world, no questions about what they are doing with their lives; everything is perfectly ordered and composed. It is a nice day.

I have never had a personal Facebook page or Instagram account, although I get the gist of the platforms through using work accounts. Although I understand the positive aspects of social media — connecting with loved ones and strangers, professional growth, being able to create and share your work with an audience, you know — I’ve never liked the idea of having another temptation to compare myself and my life with others’, when we all know we’re just posting the highlight reels, anyway (and life, if it is good and full, is certainly more than highlight reels). Twitter is the first personal social media account I’ve had. I got it four months ago for professional opportunities, and I have almost deleted it several times since. Besides having a fundamental issue with self-promotion, I don’t like the idea of a computer algorithm being able to predict things about me through information I have given up about myself through the things I like and retweet. Besides, after the initial excitement about the platform wore off, it is mostly boring, the same people speaking, the same ideas and sentiments echoed and passed around, wholly lacking in originality. And with that, there comes a disappointment and certain amount of existential dread, the letdown when things that are supposed to entertain me cease to and do not.

The Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma” explores the ways social media has been designed to be addictive and manipulative. Through the testimonies of people who helped create elements of social media and are now seeking repentance and absolution, the film exposes the ways social media algorithms are “(1) Spying on you. (2) Manipulating your feeds to keep you engaged. (3) Deepening your biases and blind spots by pushing away everything else,” according to Anthony Breznican’s article “This Documentary Will Make You Deactivate Your Social Media.” In “‘Social Dilemma:’ Netflix Film Director Explains Hidden Cost of Social Media” by Mike Brown, Director Jeff Orlowski makes the point that if you’re not paying for a product, you are the product, and whatever your preferences are that will keep you coming back will be capitalized upon.

“We are actively building systems that are causing polarization, that are causing echo chambers, that are dividing our country and our way of thinking,” Orlowski says of social media in Breznican’s article. “We have this invisible machine that is determining what people see, and it’s giving us what it thinks we want. … We’re all in our own individual feedback loops. … How do you create consensus when everybody is being fed the mirrored version of themselves all the time?”

Through our adoration of images, we have made ourselves gods. Through social media, we have set up altars to ourselves, shrines at which we worship.

My friend’s niece is an incredible person. She is a spitfire, a strong-willed honest seeker, an adept perceiver. She thinks deeply. She questions everything. She is seven years old. I hope I raise children like her, because I believe these are the kind of children who grow into adults that change the world.

At a gathering of my friend’s family that I was gifted with being present at, her niece asked who the first person God created was. After asking and asking multiple adults, she finally received an answer that seemed acceptable to her. She ran ahead full force with her next quandary, moving from humanity to the divine: “Why is God, God, and I am not?” she asked, frustrated no adult could give her an answer that satisfied her earnesty. She spun around on the floor, flailing her arms in the desire to understand.

“You’re a human,” my friend told her, with so much love and equal desire for her to receive that truth.

“But I want to be God,” she said.

And that’s one thing that amazed me about her. If only we all admitted it so bluntly.

One of the most difficult parts of being human is the suffering caused by separation. When my friend’s niece said she wanted to be God, she had just experienced her grandmother’s funeral. Separation caused by time, distance, sin or death — it hurts because we have loved or wanted to be loved. One of the noble, if not misplaced, motives of social media, perhaps, is to help us overcome this separation: through social media, one of my friends once pointed out, we never have to say good-bye to people when our lives move in different directions. Instead, we can still be vaguely familiar with what is happening in their lives, even when we are no longer a part of it. But to deny this element of our identity is to deny who we are: people who must undergo separation because we are susceptible to time. It is part of the experience of being human.

And what about when photographs build something up so much so the real experience is a letdown? Sontag writes it like this: “Knowing a great deal about what is in the world (art, catastrophe, the beauties of nature) through photographic images, people are frequently disappointed, surprised, unmoved when they see the real thing.” We expect, sometimes, for life to imitate the photos and movies, rather than the photos and movies to imitate life. We give more credence to unreality, mistaking it for reality, frustrating ourselves when the circumstances of our lives don’t turn out the way they “should be,” like the stories we’ve seen depicted to us through images.

We get it backwards, perhaps: “The primitive notion of the efficacy of images presumes that images possess the qualities of real things, but our inclination is to attribute to real things the qualities of an image,” Sontag writes.

Yet, by unmerited gift, there are some things that defy being captured, whose splendor in an image will never measure up to the unfiltered resolution of being present before it in real life. We simply cannot possess it, but must stand, frustrated and empty-handed. Thank you for this refusal to be captured, for this pure experience we must enter into, this beauty that asks us not to produce but to first receive. Thank you that not everything in the world offers itself to us so readily as we want it, when we want it, or ever or ever or ever. Thank you for all that exists outside of ourselves that will never be ours, all we somehow still get to stand in proximity to while we breathe you, in and out and in again, this oxygen.

If reflection takes us out of experience, let us not be sad that we feel like we did not live more fully; let us be thankful that in not reflecting, we lived.

In my favorite photo of you, you are standing at the top of a hill at golden hour, holding a coffee our friend drank half of on the hike up. The sun shows through the cup. Strangers look at the view, one of our friends looks at you, but you are looking at me, head tilted to the side, hand on hip, lips smiling. You are looking at me like you see me; finally.

Because it was true for one moment when my finger tapped a button on a camera, I think it is true always, even now, when we haven’t spoken in four and a half years and you live oceans away no matter which direction I travel. (If I didn’t realize then, forgive me.) I am looking for forever, I was raised on permanence, and this photo allows me to mistake the two:

Your image for you.

It is true the words say the painting is not a pipe. Ceci n’est pas une pipe. It is not a pipe. It is a painting of a pipe, an image of an object that is real and can be touched, not the object itself that can be stuffed. He is not lying.

But aren’t words also representation, art historian Dr. Steven Zucker points out, images that stand for meaning that stands for the real object in all its fullness that can be felt? Tell me, why should we believe the words that say it is not a pipe over the image that looks like it is? Aren’t letters that make up words that make up sentences that make up paragraphs and sections and stories we structure our lives around also shapes that are drawn on a page? Aren’t words and images different and the same, two ways of expressing meaning — am I right? Can any of you by worrying add a single moment to your life?

So maybe it is a pipe, or maybe it’s not. So maybe it is a pipe, and maybe it’s not. Her Majesty, the worm. Maybe the painting’s question is not what it is but how it holds this tension of what it might be. Made in the image.

Photos by Aaron Eisenhauer

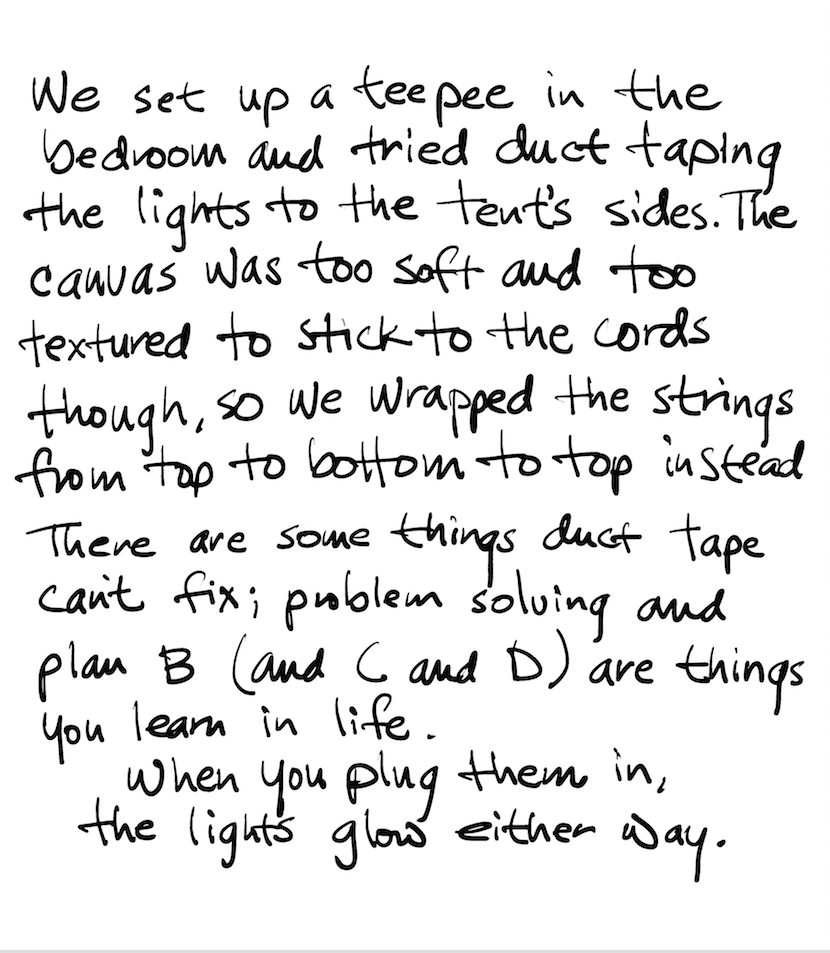

Handwriting by Gary Rust II